Flaget Retrospect

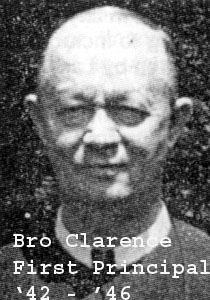

by Brother Clarence Herlihy, C.F.X. First Principal, 1942-46

One morning in late August 1942, I arrived in Louisville to concern myself with the opening of the new high school. Following instructions to contact the Chancery and let them know of my presence, I called it immediately after lunch. I was informed that the Archbishop would be glad to see me at once.

I found the Archbishop very affable. He supposed I had wide educational experience. I told him that I could recall first graders many years before and that I had concluded a series of lectures at the Catholic University just a few weeks previous, and to my best recollection I had touched every intervening rung in the educational ladder with the passing of the years. In answer to his next questions I told him I had lectured at the University on “Guidance on the High School Level.” He expressed the hope that the proposed new high school would benefit from my experience.

Getting down to business, the Archbishop told me that while the school was not yet ready for occupancy, it soon would be; that he had appointed a Priests’ Committee to see to it that the work was carried on expeditiously and successfully; that he had asked for ten brothers for the initial staff and was quite disappointed in being able to get only five, etc.

I took advantage of the letter opening to ask the Archbishop what provisions had been made for a residence for the brothers. He replied that he had been looking around for a suitable place, that he had a number under consideration but had not made any definite decision. But meanwhile, he supposed, that the brothers could be accommodated at St. Xavier. I told him that I greatly feared that such an arrangement would not be possible; that from I had thus far observed, St. Xavier was having considerable difficulty accommodating its own staff.

Little more was said about the housing matter at this first meeting. I mention it now because of the difficulties I later experienced trying to get action on what was to me very important but which was to the Archbishop, seemingly at least, a matter of little concern.

I next saw the Archbishop when he sent for me on the 14th of October. It had been announced in the papers that the school was to open on October 13th. Meanwhile, I had been dropping in at the Chancery at least once a week to find out if any progress had been made in getting us somewhere to live. On such occasions I was received by the Chancellor, Father Gerst, who was always very kind. I hammered continuously on the fact that we could bring no brothers to Louisville since there was no room for them at St. Xavier, and so left him to conclude that school could not be opened on October 13th. Anyway, I had been told by the contractor that the building could not possibly be ready on that date, so when the day did arrive, with a show of unconcern I stayed away from it. It seems, however, that several of the boys showed up for classes. Finding plasterers, painters, plumbers, electricians, etc., but no brothers, some of them bethought themselves of calling up the Archbishop to find out why the school had not opened as it was scheduled to do.

The Archbishop was quite distressed at the interview on the 14th. He still had been unable to find a suitable residence, but he was presently negotiating with three different parties and felt sure that a residence would be available in a question of days. He suggested that the brothers, meanwhile, could be housed in different neighboring rectories — one at Christ the King, one at Holy Cross, one at St. Charles Borromeo, etc. He insisted that a definite date be set for the opening and decided on October 21st.

I phoned a detailed report of the interview to the Provincial who said he would come right down. He did arrive a few days later, bringing with him three young brothers to teach at Flaget.

I had another interview with the Archbishop, in the late Spring of 1944, to discuss ways and means of handling the overflow which had enrolled for the Fall. At still another time he asked me to attend a meeting when he and the West End pastors were discussing the building of a residence for the brothers. Aside from these I usually transacted business through either Father Kieffer of the Priests’ Committee or the Chancery.

The Priests’ Committee

At the end of my first interview with the Archbishop, he told me that he would have the Chancellor bring me down to see the new school and that he had arranged with the Priests’ Committee to meet me there. He told me that the Committee was made up of three pastors from the West End: Father Kieffer from St. Charles Borromeo; Father Maloney from Holy Cross; and Father James, a Black Franciscan from St. Peter’s. I was secretly comforted at the mention of the Black Franciscan, feeling that since he was living in community himself, he would have a good understanding of community life and its material needs.

The school-to-be was the one-time residence of the Whallen brothers, influential in the political life of Louisville during some by-gone period. It was wooden, not elaborately built, but large as became, I suppose, people who did considerable entertaining. It was manifestly old and had been neglected in more recent years. Where the paint had worn off in many places, there were evidences of dry rot. On this day the interior was a veritable heap of rubble. A wrecking crew had moved in that very morning and in the intervening hours had really done themselves proud.

Having met the Committee and having little in our immediate vicinity to talk about, I veered the conversation around to what I considered the pressing need of the moment — a residence for the brothers. Father James quickly announced that he had solved the problem and asked us to follow him upstairs. He led us to the attic. It was of the old-fashioned type with its dormer windows and gabled sides and a veritable furnace on that hot summer’s day. He proceeded to point out how it could be divided into six bedrooms and then went on to enumerate its other advantages. I wondered if he were serious, and as I looked from one to the other to assure myself, I was painfully surprised to find only apathy registered on every face and to notice a silence which meant they were ready to concur in the plan if given any encouragement. I thought this was an opportune time to let them know that we would not be satisfied with just anything. I told him flatly that such an arrangement was unacceptable to me personally and that I felt sure my superiors would not consider it for a moment. I felt that I had been completely let down by the Black Franciscan.

Up until the time the school opened, the Black Franciscan stayed faithfully on the job, but he gradually lost interest until finally he seemingly became quite irritated ever when I spoke to him over the phone. He was never called, of course, unless in cases of absolute necessity, but in the beginning, when so many incidentals had to be taken care of, the Committee had to be consulted frequently. The impression always persisted with me that he was out to show the Archbishop that his choice of a Franciscan as a committeeman was a most fortunate one. He seemed anxious to constitute himself the front man of the Committee, an arrangement to which, I believe, the others readily agreed. Unfortunately, many of his ideas about how things should be done were extraordinary to say the least. They had generally one redeeming feature, however, namely that had they prevailed, they would have saved lots of money for the Archdiocese. The business of turning the attic into a residence for the brothers was a case in point.

To provide playing space at the high school, several large trees on the property were uprooted, but left lying where they had fallen. Some boys would scramble up on those prostrate trunks while others would playfully sneak up behind them and push them off. When accidents and near accidents began to multiply, I began to ask both Father Kieffer and Father James about having them removed. It was decided that the matter should be put in Father James’ resourceful hands. He was to contact a Father Canue who had much influence with the city authorities and would enlist their aid in the undertaking.

Nothing happened as the days and weeks became months. Finally, I called the Fire Chief (Krusenklaus) and asked him if he would have his department play their powerful hose on the roots to remove the tons of dirt adhering to them. He said he would gladly lend us the hose, but that he was allowed to use city water only to put out fires. I immediately called the City Water Department and got permission for the water. Later, I called the head of the Parks Department, who sent the men and necessary equipment to take the trunks and carry them off somewhere into Shawnee Park. This “direct approach” had to be again brought into play when it was found necessary to have the city install a pole and light in an alleyway adjacent to the school.

The Provincial was on hand the day we moved into 527 South Western Parkway. Before leaving, he emphasized the fact that he wanted a chapel on the premises as soon as possible. The matter was immediately brought to the attention of the Chancery and the Committee. As the months of pleading for action came and went, the Provincial became increasingly insistent. Finally, the Black Franciscan again came up with a bright idea. The now unused garage, he said, was just the place for the chapel, and so he ordered the caretaker (Mr. Rhodes) to give it two coats of yellow paint. A carpenter came to make a table which was to be the altar.

The Provincial showed considerable displeasure at the arrangement and said he would protest it to the Archbishop. Summer had come by now and the carpenter was with us again, this time building partitions on the third floor, designed to make two large rooms into four smaller but quite comfortable ones. I had him partition off part of our large community room to make a chapel large enough to accommodate the community at that time. I sent the bill to Father Kieffer who paid it, I’m sure.

It was not easy to get suitable furniture. The War was on and the supply of civilian commodities was indeed low. The Committee delegated me to try to pick up what I actually needed and it occurred to me immediately that we might need beds. It was at this point that the Black Franciscan gave what was to me the crowning proof of his resourcefulness and ingenuity. He called me up to strongly suggest that I get hospital beds. I asked him to repeat to make sure I was getting it right. “Yes!” he said. “Hospital beds.” They would have, he said, two capital advantages: It would be easier to clean the floor under them, and the brothers would be unable to sit on the sides of them and injure the mattresses. Exasperated, I asked: “How would you like to have to use a hospital bed?” He had a ready answer to that one. He assured me that his was a hospital bed; that the Black Franciscans were using them in their training school, and seminaries and all the way up, and were finding them very satisfactory.

I got the beds. Everything about them was wood except the springs which were inferior and were set into wooden frames. Due to the War, however, they were the best I could find, and needless to say, they were not hospital beds. If the Black Franciscan was not very helpful, he was unusual anyway.

The contribution of Father Maloney, the second committeeman, to the growth of Flaget, was much less than negative. He had opened a high school in his own parish in 1941 and so its entering class had finished its freshman year when Flaget opened in 1942. From what I gradually gathered, his main reason for opening this high school was to satisfy a complex he had developed against St. Xavier. It was now beginning to dawn on him that he had bitten off far too much and so he happily hailed the opening of Flaget as an opportunity to close shop. Were it not for this Flaget would undoubtedly have opened with freshmen only, which would, of course, have been more desirable and better. Except for one occasion to which we will allude later, he came around only when he was forced to. What contacts he had with the other members regarding school matters, were made mostly, I was led to believe, by phone.

The third member of the Committee, Father Kieffer, was by far the best of the three. He displayed practical common sense, except on a few occasions when he seemed to have been prevailed upon by the other two. He was the treasurer to whom was turned over the tuition money. The Archbishop had ruled that the tuition was to be five dollars a month but that no one was to be refused admission who pleaded his inability to pay. He expected some cheaters, he said, but even the cheaters must be admitted. All a non-payer or one seeking special rates had to do was to bring a note from his pastor stating the conditions. One pastor, Father Hannon of Sacred Heart, knowing that he would be deluged with requests from both rich and poor, refused to sign any notes. One woman wanted to know why she had to pay any tuition since she had already contributed to the “drive.” I believe the Archbishop hoped to have each parish assume the deficit caused by those of its members admitted under the special conditions. Subsequent events disproved his optimism.

At a time, therefore, when expenses were great and revenues were small, Father Kieffer was hard put to it to make ends meet. At times when the funds gave out completely he presented some of the bills at the Chancery . They were paid, but with the understanding that the Chancery was to be reimbursed when funds again became available. It was not too long before he was expressing himself as being heartily sick of his job. He would often express himself : “If you need it, get it,” or “If it must be done, do it.” However, he would usually say that he would get in touch with the others and that invariably meant delays, sometimes protracted ones. He informed me once, perhaps facetiously, that Father James must not be disturbed on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays since those were his days for playing golf. It was at about this time, when the school population was close to 500, that I spoke to him about getting a secretary. A few days later he phoned to tell me that Father James had said that he failed to see why I couldn’t attend to the secretarial work myself since I had nothing else to do.

Other Priests

My first “brush” with the Priests’ Committee, along with similar experiences with the passing of time, convinced me that I must perforce re-evaluate conditions as they actually existed in connection with the opening of the new high school. Finally, a far more realistic picture began to take shape.

My thought at the beginning, hazy and considered only superficially even before leaving Baltimore, was that the event would be hailed with becoming enthusiasm, especially on the part of the clergy. Hitherto there had existed only one Catholic high school for boys in Louisville and the resources of this one had been overtaxed for years. Still it could hardly accommodate half the Catholic boys who should have been getting their secondary education under Catholic auspices. A similar situation of course, existed and still does exist in many other places, and the general understanding is, I believe, that this situation is regretfully accepted but only because adverse circumstances prohibit the opening of more Catholic schools. It should naturally follow therefore, that in their zeal for souls, the clergy would rejoice and give due thanks to God whenever such schools are brought into being.

It was, I believe, the hope of the Archbishop that genuine enthusiasm could be aroused among the pastors of the West End parishes — the parishes which stood to benefit most from the new high school. To get them to cooperate, however, he needed to destroy a chronic parochialism which had grown and developed among them for years, and had perhaps, been encouraged unwittingly by himself. Judging from the fact that few of them needed the ministrations of more than three priests, the parish populations were small, but rare indeed was the parish which could not boast of a quite magnificent church, rectory, and school. Each pastor had meanwhile withdrawn himself from active life to one of comparative luxury, encumbering himself only with the ordinary priestly functions. When therefore, it was proposed to them to join in a common effort, they were not conditioned to accept the situation. So accustomed had they become to working exclusively for themselves individually, that they seemingly shrank form anything suggesting cooperation.

But where had these pastors gotten the means to surround themselves with the material comforts mentioned above? Apparently from “Bingo.” So highly indeed was it regarded as a source of revenue that by agreement the larger parishes had so allotted the seven nights of the week that each would have its own “bingo night.” Each had organized its own “hard core” clientele (our housekeeper was a “card-carrying” regular at Holy Cross, St. Anthony’s and St. Charles’) and were ever reaching out after larger crowds by offering bigger attractions and more expensive prizes. On its appointed night, the parish would cover all available space in the classrooms, hallways, and auditorium of its school, with tables and chairs; loudspeakers were installed and patrons packed in. It was really big business.

I mention the above because of the impact it had on us later, at Flaget, whenever we held affairs or just ordinary meetings. No matter on what night we held them, we were sure to offend someone. Some of the clergy, Father Fallon of Christ the King, for instance, usually expressed himself quite forcibly and bitterly to his parishioners attending our meetings on his night.

I always got along well with Father Gerst, the Chancellor. I visited him often in the beginning, principally to keep the pressure on about getting us a residence. Moreover, any little news connected with the school, and especially anything I intended to do, like organizing a PTA, was always made the subject of conversation, and in such a way that I could feel morally certain the information would be conveyed to the Archbishop. This was done to forestall distorted information from other possible sources and to give the Chancery the opportunity to object to any contemplated action of which it did not approve.

Very early in September, 1942, it was announced in the churches that registration for the new high school would be held at Christ the King on a certain date. It was then I met Father Fallon who invited me to lunch in the rectory. In this first conversation he was critical of many things, including the efforts of the Archbishop and the committee members knew nothing at all about the business on hand but there was a man that did know who was not only passed over by the Archbishop but was actually told to keep “hands off.” His name, he said, was Father Pitt.

I had heard of Father Pitt. Before I had left Baltimore, the Provincial had mentioned the name and said Father Pitt might prove to be a meddler. Father Fallon had no idea how much I was relieved by his tale of woe. Father Pitt hovered around considerably in my time but never interfered.

About the same time we took up residence at 527 South Western Parkway, Father Rausch was assigned to Christ the King as an assistant. His principal duties, however, as told by the Archbishop to the Provincial were to be two-fold: First, to be responsible for religious instruction in the school; and second, to be chaplain to the brothers. When we were ready for him he would give us daily Mass. For this we were to give him one dollar per day.

The Provincial refused the dollar-a-day arrangement, so it was eventually decided that we should have weekly Mass, read by a priest from Christ the King, and calling for no stipend. The rest of the week we were to attend Mass in the church. Father Rausch started his school assignment with the zeal of a St. Paul. He took both freshman classes numbering about seventy, on the first day, and both sophomore classes, numbering about fifty, of the second. He told me after this latter class that he felt that he must come every day and would need at least one hour daily as “there is so much to be done.” I told him that we could not possible extend his time beyond on half hour and that much more could be done in that time if he took them in smaller groups. If for instance, he would take one freshman class on Monday and other on Tuesday; one sophomore class on Wednesday and the second on Thursday, leaving Friday free, better results would be forthcoming. He reluctantly agreed to give my recommendation a try. As I greatly feared, Father Rausch’s zeal soon began a downward spiral, and so consistently that a new low was recorded after about each succeeding session. He began complaining to the Chancery of the load he was carrying, so Father Spalding was sent from St. Columba’s to ease the burden. Then the boys began “acting up” and were becoming increasingly hard to handle. Finally arrived the day when he came in to say that the conduct of some to the boys was insulting and demanded that something be done about it. He seldom came after that.

We Organize Our PTA

Even while we were still residing at St. Xavier, the Provincial strongly suggested that a PTA be organized at Flaget. He enumerated many benefits that might possible accrue from such a body. Meanwhile, I had been observing a well-organized and smoothly running PTA in operation at St. Xavier and was properly disposed to form ours at the earliest opportunity.

And if I may digress for a moment at this point, I would like to state that our PTA was definitely effective and amply repaid us for every ounce of energy we ever expended on it. We always kept to the front the primary purpose of the organizations which was have the parents meet the teachers and discuss in a constructive way the boy and his problems, if he had any. The boy was the real beneficiary. The meetings were always very well attended; the teachers were always required to attend.

To resume, I set a date for a Parents’ night, and told the boys we would be delighted to have their parents come to inspect the school and to meet the teachers. The response was really generous. We seated all we possible could in our largest classroom; the others stood. After the introductions I asked what they thought of creating a PTA. The idea was enthusiastically received. A date was then set upon which we met; elected officers; approved a set of by-laws, and began to function. Incidentally, the by-laws provided that the principal of the school was, ex-official to be the treasurer.

At the first regular meeting it was recognized that money would be needed for current expenses — not a great deal to be sure, but since it was decided to serve refreshments after each business meeting while parents and teachers were in consultation, and since cards had to be bought and mailed to members as reminders, when the dates for monthly meetings were approaching, some money had to be available. It was therefore, decided to hold a card party on some not-too-distant date, by which it was hoped that enough would be realized to tide the organizations over for about a year. Some blind instinct warned me that since it was a question of raising money I had better make known all plans in detail to the Chancery.

I couldn’t swear to it now, but I am almost certain that the publicity committee took steps to have the party announced in all the West End churches. All were exhorted to talk about it and to lose no opportunity to give it the widest publicity, and since many men and women prominent in the life of the different parishes were very active members of the newly-formed PTA, no one living in Louisville’s West End could have failed to know of the intended party.

Mr. Henry Mangeot, the president, appointed Mr. Jim Hargadon, the vice-president, as general chairman. The latter was an organizer without a peer, and he soon had every member on one committee or another and putting forth his or her best effort. Even without Mr. Hargadon’s dynamics, however the circumstances of the situation were tailored to generate enthusiasm. Here was a new organization whose members were the cream of the fine young married people of the West End parishes. They had but recently become acquainted and had found one another very acceptable. They now only need to join their efforts in some common enterprise to solidify their friendship and union. It would be impossible to imagine anything more motivation than a project for the betterment of their high school, and ultimately of course, of their children.

Some of the West End curates attended the party. I was glad to see Father Maloney come in, and told him so. He seemed to pre-occupied and in a hurry. He brushed past and was apparently more bent on estimating the size of the crowd and appraising the setup generally than in anything else. He was out of the place and away again in a question of minutes.

Mr. Hargadon found out at the last moment that he could use another wheel. He jumped into his car and rode down to St. Charles. Father Kieffer met him; brought him over the church, and procured for him the sort of wheel he wanted. Other churches like St. Anthony’s and even St. Boniface, lent us chairs and gave whatever material help they could.

The party was a complete success; over $1,100 was cleared; and when the members scattered to their homes, the felt they really had done themselves proud. We who stayed behind to take care of the details were commenting on the wonderful news we had for the Archbishop, the priests, and the world generally.

The following day was Saturday. The first sour note was sounded when a Mrs. O’Bryan from Holy Cross phoned me.

“Have you heard what Father Maloney said?” she asked. “No,” I told her. “What did he say?” “Well,” she continued, “he was taking to some ladies after church this morning, and he told them that Flaget was not like St.X, and that the card party money didn’t belong to you, and that you won’t be allowed to send it to Baltimore.”

I got her off the line as quickly as possible, and in perhaps an hour I was presenting myself at the Chancery. Father Gerst met me as usual. “Father,” I said, “I have good news this morning. The card party was a real success.” “So Father James told me,” he answered, rather dolefully, I thought.

Pretending not to notice his attitude I continued: “Yes, we cleared (here I mentioned the exact sum). “Whew!” he exclaimed. “I know many parishes that don’t do that well.”

Father Gerst was not at all as cordial as was usual with him. I was mystified. Perhaps I, a newcomer, had unwittingly broken some diocesan rule or practice, but then the people who had run the affair — and there were so many seemingly intelligent people — surely would have told me … It was all too much for me, so after expressing the belief that the Archbishop would be delighted to hear of our success, I betook myself home to await developments.

I did not have to wait too long. Within the week, certainly, Father Kieffer phoned to say that a message from the Chancery had instructed him to take over the custody of the $1,100. He was quite apologetic about it as if he felt the idea was stupidly conceived. I told him of course, that he could have the money at any time, so that afternoon when he came, I gave him a full statement of receipts and expenditures and a check for the balance. That done I assumed the role of neutral observer, hoping meanwhile that the PTA would weather the storm I saw impending.

When of necessity, I told Mr. Mangeot of the arrangement he was furious. He immediately went to Father Kieffer for an explanation, and from what I was able to glean afterwards, their conversation was decidedly bitter. Feeling that he was not given satisfaction, Mr. Mangeot went from there to the Chancery.

The news soon became public. The initial bewilderment of those affected soon turned to resentment at what they considered the arbitrary action of the Archbishop. There were in circulation several garbled versions of what had taken place; feeling generally ran high.

Meanwhile the Archbishop must have learned of what was going on. Second thought must have convinced him that he had blundered. He had been taken in by some such story as the one concocted by Father Maloney about the money going to Baltimore. He had undoubtedly misunderstood the motives for the complaints emanating from Father Maloney and thought they indicated a growing interest in the school, and he wanted, by all means to develop that interest, and so he had sided with Maloney. Now, disillusioned somewhat after the Mangeot visit, he told the Priests’ Committee that it must make an explanation to the PTA.

One day, without previous notice, I was honored by a visit from the entire Committee — it was indeed unusual to see all three of them at one time. With a show of belligerency they wanted to know what all the “shooting” was about. Did the PTA think it was going to run the school, etc.,etc. I offered my services in arranging a meeting between them and the PTA officers.

The meeting was held in the Holy Cross rectory. Mr. Mangeot, Mr. Hargadon, and Mrs. Agnes Rush (secretary) represented the PTA; our Priests’ Committee was on hand to represent the Archdiocese of Louisville.

There was no belligerency this time from the Committee, but rather an evident willingness to overlook everything and call the whole thing off. Father Maloney did not speak once; the Black Franciscan essayed an occasional grunt of approval, so that Father Kieffer was given no assistance in his efforts to parry the logic and incontestable declarations of Mr. Hargadon, the PTA spokesman. He questioned the propriety of their taking over the money; he told of the humiliation unjustly imposed on the PTA; he said that from a young and vigorous organization with potentialities for immeasurable good the PTA had bogged down from sheer discouragement and was carrying on with the feeling that they were “under a cloud.” “And why?” he wanted to know. Father Kieffer with a show of humor which was manifestly forced professed to see nothing at all in the situation. Mr. Hargadon replied that it was no laughing matter and that the only reasonable solution of the situation would be for the Committee to appear before the PTA and explain everything.

They came all right. (Father Gerst later told Mr. Mangeot they didn’t want to but the Archbishop insisted.) I remember how they expressed surprise at they attendance. ( We always had about 100.) The Black Franciscan spoke, keeping scrupulously away from any mention of the money. He told the group how in his mind the diocesan high school differed from the private school.

The reaction to the speech could, I believe, be well summed up in a remark made to me afterwards by a Mrs. Bonn: “Brother, I know you don’t want to talk, but you know that Father James did not tell us why they took over the money. That’s what we still want to know.”

What eventually became of the $1,100? The PTA continued to spend it, meanwhile sending the statements faithfully to Father Kieffer. I believe it began to dawn on him that he was stuck with an unnecessary new job which still carried with it considerable odium, and this latter was now, in large measure, directed to him since the others had quietly effaced themselves. On one occasion sixteen dollars of PTA money reached my hands from some source now forgotten, so I brought it down to him. I was not prepared for the reaction. He really flew off the handle. He told of the added work, the irritations and the humiliations visited on him because he happened to be custodian of the PTA funds. He flatly refused to have any part of the sixteen dollars.

A few days afterwards, undoubtedly with the full knowledge of the Archbishop, he presented me with a check for the balance remaining of the $1,100, and said he never wanted to hear about it again. Thus the incident which I still believe was created by Father Maloney to stop the PTA cold before it could offer competition to his bingo, was happily closed.

Later, when another organization, the Flageteers, had to be brought into being to promote athletics in the school, I went to Father Kieffer as an emissary of the proposed Flageteers and asked him to get from the Archbishop the answer to two pointed questions: First, would the organization be permitted to run social affairs for the purpose of raising money; and second, would the organization be allowed to control its own funds.

There was no quibbling this time. The answer to both questions was a ready affirmative. Later he very graciously received the two leading Flageteers, Messrs, Ed Roby and Henry Mangeot when they went to tell him of the organization’s intention to purchase ground for a future stadium. At its first public meeting, inaugurating a membership drive, a letter was read from the Archbishop extolling the Flageteers and giving the organization his blessing.

At Random

In anticipation of your first junior class in 1943, we had to install scientific equipment. So that our needs could be clearly presented at the Chancery, I asked three scientists from the St. Xavier staff to study the situation, taking into consideration our available space, the size of the class, etc. They estimated an initial expense of about $3000. At my further request, they reviewed the situation and after considerable and painstaking effort, arrived at approximately the same figure.

To raise the money the Archbishop gave orders that the nine parishes join in some money making affair. A preliminary meeting of the pastors or their representatives was held at St. Anthony’s. It was there decided to form a committee in each parish and to hold another meeting later, at which time each parish should be in position to make known what its contribution would be.

Both priests and lay committee members were present at the second meeting, and it had not progressed very far before it was plainly evident that the party was going to be a flop. While every parish, conforming with the orders of the archbishop was represented, many it seemed, had done nothing to generate enthusiasm for the venture and were prepared to promise only a token contribution. I can recall Father O’Connor of St. Benedict’s expressing the opinion that Christ the King might reasonably be expected to do something more than to operate a wheel. Father Fallon was not present to argue the point, but knowing him as I did, I thought he was making a rather generous gesture.

The party which was in the nature of a carnival, was held in St. Anthony’s hall, each parish working exclusively on its own. About $1,500 was realized, more than half of which came from tickets sold by Flaget students. Had they been able to pull themselves away from their pitifully narrow parochialism, the sum could have easily been $15,000. It was the only affair of that kind held in the interest of Flaget during my tenure there.

It was in September, 1945, that priests began teaching at Flaget. This came about because of the usual dilatory methods of the ordinary. Beginning early in June I kept reminding him continuously that since he wanted us to refuse nobody, the enrollment for the coming school year was going to be heavy. Additional brothers were available for the staff, but the same old vexatious problem of inadequate living quarters was still with us and the Provincial was willing to wait up to a certain point for the Archbishop to solve it. The Archbishop wrote to me during the summer asking me to be patient with him. My final answer came on the day school opened when four young priests walked into my office. Three of them said they suspected that they were sent down to help out. The fourth, Father Zahner said he was called just twenty minutes before and was told to report at Flaget, but he was not told why.

The only redeeming feature of the arrangement was that it gave us sufficient staff members for the moment. The disadvantages, on the other hand were many indeed, including the fact that they were not prepared for the work and generally disliked it; they could teach only certain subjects and it was only the exceptional ones among them that could be trusted with any but freshman classes; and due to the fact that they were all regular assistants here or there they continued to be burdened with parish activities and could not attend such necessary functions as PTA and teacher’s meetings. Moreover, despite the most cordial relations, the situation never came close to the ideal thus perhaps giving some weight to a sage remark once passed by the Black Franciscan: “Brothers and priests don’t mix.”

For the first few days at Flaget we carried our lunches from St. Xavier. The cook there, however, reasonably enough, declared that feeding the large staff at St. X was about as much as she could physically handle, so we had to look for nourishment elsewhere.

Since there were no eating houses serving noon-day lunches in the neighborhood, we besought ourselves of asking the Sisters of Loretto Academy to help us out because we knew they served lunches to their own students. They were most kind for as long as we needed their help. When the priests were added to our staff, the Sisters did them a like services.

Page Count Since January 1, 2025: 222 |